Regulatory authorities in Britain, the US, Singapore and various other countries are engaged, more or less enthusiastically, in investigating the extent of the now fully recognised scandal of Libor rate-fixing that has been taking place over at least the last seven years. It was hardly a secret, and had been openly discussed in the financial press since at least 2008. At the end of 2008, the governor of the Bank of England, Mervyn King, no less, described the Libor to Parliament in the following terms:

“It is in many ways the rate at which banks do not lend to each other, and it is not clear that it either should or does have significant operational content. I think it is convenient, very often, for people to justify what they do for other reasons, in terms of Libor, but it is not a rate at which anyone is actually borrowing. It is hard to see how it can actually have much of an impact.”

Yet although everybody knew that Libor – as indeed is the EU equivalent Euribor – was an entirely arbitrary and fictitious rate at the time Mervyn King made these remarks (particularly since banks were not lending much to each other at all, and certainly not at the Libor quoted rates, or without security), it happens to be a base rate that is generally accepted all over the world to determine the interest rates appropriate for a vast array of financial instruments.

In many ways, Libor was an accident waiting to happen:

“And yet, despite their inherent fuzziness and lack of ‘significant operational content’, despite the lack of formal checks on banks’ internal procedures for coming up with these rates, Euribor and Libor are the benchmark for pricing transactions worth trillions of dollars. US dollar Libor, for example, is the basis for the settlement of the three-month Eurodollar futures contract, which had a traded volume in 2011 with a notional value of $564tr, according to the CFTC [the US Commodities Futures Trading Commission].” (‘Inconvenient truths about Libor’ by Stephanie Flanders, BBC News Online, 4 July 2012)

“Created in simpler times, Libor was designed for pricing loans and deposits. Over time, derivatives based on Libor have become dominant. Perversely, the cash market on which Libor is based now supports a vastly larger derivatives market. Generations of quantitative experts have built elegant models based on advanced mathematical techniques to price complex derivative instruments on a deeply flawed and easily manipulated base.” (‘A tricky path to tread if the Libor fix is to be fixed’ by Satyajit Das, Independent, 1 September 2012)

In theory, Libor (London Inter Bank Lending Offered Rate) is the average rate of interests that big banks have to pay if they borrow from each other. As is explained by Richard S Grossman:

“Libor is supposed to measure bank borrowing costs – that is, the interest rates banks charge each other to borrow money. It is calculated by asking a handful of large banks how much they estimate it would cost them to borrow funds. The highest and lowest 25 percent of submitted estimates are thrown out; the average of the remainder is Libor ...

“Because so much money is riding on Libor, traders have an incentive to pressure their banks into altering submission estimates to improve their profitability. Even a small movement in Libor could lead to millions in extra profits – or losses – for banks.” (‘Mob can help fix troubled Libor, the benchmark interest rate’, investors.com, 8 July 2012)

So how are Libor rates fixed?

In these circumstances, it is not surprising that a ‘culture’ had grown up among those whose job was to report their bank’s borrowing rates to the British Bankers’ Association. Those submitting the figures became amenable to requests from traders (from their own bank and sometimes others) to submit relatively higher or lower rates than the real ones – the aim being to assist the traders to turn in a tidy profit from their speculative activities.

A whole series of emails have been produced in the case of Barclays Bank that provide evidence of traders asking rate reporters for favours and thanking them profusely when they comply. “In one, a trader at a different bank wrote to ‘Trader G’ at Barclays: ‘Dude. I owe you big time! Come over one day after work and I’m opening a bottle of Bollinger.’

“Other emails revealed how they would ‘shout’ across the desk at each other to ‘beg’ for the interest rate to be fixed at a certain level in the hope of making millions for themselves.” (‘Boring Bob: Former Barclays boss Diamond fails to dish the dirt on politicians or bankers despite grilling by MPs over rate-fixing scandal’ by Rick Dewsbury, Mail Online, 4 July 2012)

Former Barclays CEO Bob Diamond claimed not to know that there had been such goings-on at his bank during his stewardship. He said he had felt physically sick when he saw these emails. Cynics, however, might possibly conclude that the ‘sickness’ was caused by the publication of evidence of the Bollinger-fuelled indiscretion of the Hooray Henries employed by the bank on vast salaries, rather than by revelations of rate-fixing that almost everybody in the business had known about for years.

Because Libor is fixed on the basis of eliminating the 25 percent of highest returns submitted and well as the 25 percent of lowest returns, rate fixing can only happen if traders at different banks co-ordinate with each other to produce higher or lower rates to order across the board. As Nigel Lawson (Conservative Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1983 to 1989) correctly pointed out, the scandal was a “conspiracy among people in a number of banks. No one bank can fix the Libor rate on his own. It requires collusion.”

Ongoing investigations will perhaps reveal who at least some of the colluding parties are, but it seems probable that most of the banks involved in setting the Libor rate will turn out to have been tainted – and that will include US and European banks too, not just British ones. Lawson went on to remark that “what they were doing was for private gain and it was totally disreputable and there’s no public interest defence at the minute”.

The implication of this would seem to be that the whole thing can be blamed on a few dishonest individuals chasing ‘private gain’, rather than the banks themselves. However, the condition for the traders to make money has always been that their employer should make money first, and only if their employer makes plenty of money does the trader get his million pound bonuses. It was always therefore very much in the interests of the banks not to investigate rumours of rate rigging too rigorously!

Libor following the onset of the crisis

Once the financial crisis erupted in 2008, Libor began to play a crucial role in helping banks weather the crisis, as a means of helping them to restore the capital lost through defaulting debts. Fiddling Libor became a matter of life or death – on both sides of the ocean.

The crisis, it will be recalled, expressed itself principally in its initial phases in debt default radiating out from the notorious US subprime mortgages. Huge amounts of capital were lost as a result of bad debt, with the banks, as major lenders, being particularly vulnerable to this. However, most British banks need to borrow vast sums to keep their businesses going (including their lending business), and it is paradoxically therefore more beneficial to them for interest rates to be low (so as to borrow more cheaply) than for interest rates to be high (when they can charge more to customers for what they lend to them).

It is obvious from the table below which banks have a special interest in keeping interest rates low:

With the advent of the crisis, when lenders began to worry about the financial viability of banks that were exposed to losses on financial instruments loaded with worthless subprime debt, interest rates started to climb, since interest rates are always significantly higher on what are perceived to be risky loans than those that are perceived to be safe. But the very fact that the interest rates charged to any borrower are high sends a signal to the market that the borrower in question has problems and is a risky customer – which drives the interest rates that borrower has to pay even higher.

It follows that, in order to be able to continue to borrow at relatively low rates of interest, it very much suited the various banks to signal to the market that they were still institutions very much trusted by lenders. So in putting in their returns for the purpose of the calculation of Libor, all the banks were signalling relatively low interest rates.

Dr Paul Craig Roberts and Nomi Prins of Global Research further explain how and why banks, regulators and governments all had mutual interests in any manoeuvres, including illegal manoeuvres, to keep interest rates low:

“Indicative of greater deceit and a larger scandal than simply borrowing from one another at lower rates, banks gained far more from the rise in the prices, or higher evaluations of floating rate financial instruments (such as CDOs), that resulted from lower Libor rates. As prices of debt instruments all tend to move in the same direction, and in the opposite direction from interest rates (low interest rates mean high bond prices, and vice versa), the effect of lower Libor rates is to prop up the prices of bonds, asset-backed financial instruments, and other ‘securities.’ The end result is that the banks’ balance sheets look healthier than they really are.

“On the losing side of the scandal are purchasers of interest rate swaps, savers who receive less interest on their accounts, and ultimately all bond holders when the bond bubble pops and prices collapse.” (‘The real Libor scandal ... ‘with the complicity of the Bank of England’, 15 July 2012)

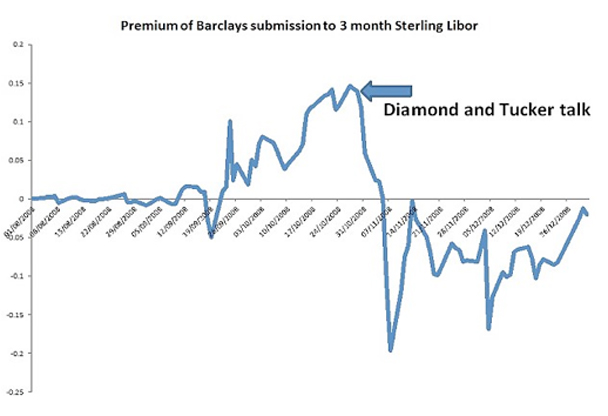

Barclays, however, although it will always be indelibly the first bank to be associated in people’s minds with the Libor scandal, was in fact one of the last to join the party. For a long time it was routinely signalling a rather higher rate than the rest of the banks.

This did not at all suit the government. It needed interest rates to be low in order to maintain the cost of servicing public debt at an affordable level; and it needed not to have to rescue any more distressed banks. Low interest rates could also make a huge difference in whether businesses could keep going or whether they were forced to shut up shop, dumping their employees onto the unemployment register to swell the government’s welfare bill. In this context, it would seem that Barclays was, not to put too fine a point on it, officially instructed to fiddle its Libor returns.

Of course, there is nothing so crude as a formal written instruction to Barclays to do this. The only written evidence is in the form of an email sent by Bob Diamond (then CEO of Barclays Capital, the parent company of the group) to John Varley, then chief executive of Barclays plc, advising him of the purport of a conversation he had had with Paul Tucker of the Bank of England. This email is not unambiguous:

“Bank of England, 29 October 2008. Further to our last call, Mr Tucker reiterated that he had received calls from a number of senior figures within Whitehall to question why Barclays was always toward the top end of the Libor pricing ... I asked if he could relay the reality, that not all banks were providing quotes at the levels that represented real transactions, his reponse ‘oh, that would be worse’.

“I noted that we continued to see others in the market posting rates at levels that were not representative of where they would actually undertake business. This latter point has on occasion pushed us higher than would otherwise appear to be the case ...

“Mr Tucker stated the levels of calls he was receiving from Whitehall were ‘senior’ and that while he was certain we did not need advice, that it did not always need to be the case that we appeared as high as we have recently.”

Of course, nods and winks are inherently more ambiguous than clear instructions. But the statistics speak volumes as to how Mr Tucker’s intervention was understood at the bank: ie, the other banks may be fiddling their returns – it would be ‘worse’ if they didn’t – and there was no ‘need’ for Barclays to be out of step – so Barclays, as far as the government and the Bank of England were concerned, were free to join the fiddle.

Let the figures speak for themselves:

The government, of course, covered its tracks pretty efficiently, but some evidence was nevertheless forthcoming of its involvement:

“The Daily Mail revealed yesterday that Baroness Vadera, then a Cabinet Office minister, prepared a paper days after the conversation between Mr Tucker and Mr Diamond which concluded: ‘Getting Libor down is desirable.’

“A spokesman for the peer said: ‘She has no recollection of speaking to Paul Tucker or anyone else at the Bank of England about the price setting of Libor.’

“The Bank of England refused to comment.”

Baroness Vadera is known to have been a close associate of Gordon Brown’s ... The whiff of cordite is unmistakable.

And if high interest rates did not suit the government, neither did it suit the big investors, the bourgeois class as a whole, as Paul Craig Roberts and Nomi Prins explain:

“The question is, why do investors purchase long-term bonds, which pay less than the rate of inflation, from governments whose debt is rising as a share of GDP? One might think that investors would understand that they are losing money and sell the bonds, thus lowering their price and raising the interest rate.

“Why isn’t this happening?

“PCR’s 5 June column, ‘Collapse at hand’, explained that despite the negative interest rate, investors were making capital gains from their Treasury bond holdings, because the prices were rising as interest rates were pushed lower.

“What was pushing the interest rates lower?

“The answer is even clearer now. First, as PCR noted, Wall Street has been selling huge amounts of interest rate swaps, essentially a way of shorting interest rates and driving them down. Thus, causing bond prices to rise.

“Secondly, fixing Libor at lower rates has the same effect. Lower UK interest rates on government bonds drive up their prices.

“In other words, we would argue that the bailed-out banks in the US and UK are returning the favour that they received from the bailouts and from the Fed and Bank of England’s low rate policy by rigging government bond prices, thus propping up a government bond market that would otherwise, one would think, be driven down by the abundance of new debt and monetisation of this debt, or some part of it.”

Thus it is clear that if the British authorities were using Libor fixing to manipulate the market, the US was achieving the same goal through manipulation of interest rate swaps. Roberts and Prins conclude: “We have learned that the Fed has been aware of Libor manipulation (and thus apparently supportive of it) since 2008. Thus, the circle of complicity is closed. The motives of the Fed, Bank of England, US and UK banks are aligned, their policies mutually reinforcing and beneficial.” (Op cit)

Enter the US regulators

The overwhelming consensus of the financial press in Britain today, however, is that US regulators are quite rightly incensed by the improper behaviour of British banks, not only over the Libor scandal, but also in laundering Mexican drug money (in the case of HSBC) and in breaching sanctions imposed by the US on Iran (in the case of Standard Chartered), thereby of course promoting terrorism and weapons of mass destruction.

The British bourgeois media are all deeply apologetic about all of this, almost unanimously grateful to the efficient US regulatory system for exposing improper bankster behaviour that the lax UK regulatory authorities had turned a blind eye to, followed by strenuously urging the British government to take stern and immediate measures to remedy matters before London is undermined in its role, critical to the health of the British economy, as one of the world’s foremost financial centres. The British bourgeoisie is obviously scared to death of the punitive measures which Uncle Sam might put in place and is very humbly apologetic in the hope of softening the blows that the US is now showering upon it from motives far from noble, as will be seen.

If today the cosy relationship between British and US banks, the British and US regulatory authorities and the British and US governments are breaking down, it is undoubtedly the deepening crisis that makes it difficult for them to maintain their cooperation in the light of their competing interests in the market place, where contradictions continue to sharpen.

By suddenly getting on his high horse about Libor rate fixing, Tim Geithner of the Federal Reserve, who in 2008 confined his concern about the Libor rate to firing off an email to the Bank of England which was never followed up, is able to set the ball rolling for various different departments of US government and finance to impose multi-million dollar fines on Barclays, secure also in the knowledge that they will be able to follow this up with more fines on other banks which necessarily must also have participated in the exercise. RBS has already been collared. But the money-gathering exercise is not going to stop at Barclays, from whom the record sum of $450m has been collected by way of fine for the benefit of US and UK authorities.

“Seven of the world’s largest banks are facing fresh scrutiny from a powerful US state prosecutor over their role in the alleged rigging of Libor, the lending gauge at the centre of an international scandal.

“Eric Schneiderman, New York attorney-general, has sent subpoenas to Deutsche Bank, Citigroup, JPMorgan Chase, Royal Bank of Scotland, Barclays, HSBC and UBS in the latest probe into banks’ setting of the London Interbank Offered Rate, according to people familiar with the matter and regulatory filings.” (‘Seven banks in New York Libor probe’ by Shahien Nasripour and Tracy Alloway, Financial Times, 16 August 2012)

In their anxiety to collect cash from foreign banks, the US authorities are having to include a couple of US banks as well, since the fact that they were right up there in front with the rest will be impossible to hide, the wider this can of worms is prised open.

If low interest rates are going to cease to be nice little earners for the UK and US governments, what is more natural that they should turn to mega fines for a new source of income? However, there are signs of strain in their relations of cosy cooperation, as the US authorities go beyond the Libor rate fixing to accusations of sanctions busting and money laundering against Standard Chartered Bank and HSBC respectively, again seeking massive payouts from the banks in question.

When it comes to sanctions busting, there is also tension between the US government and various European governments, as few of the latter are as keen on preparing for war against Iran, in particular, as the US administration. The war in Iraq has taught them that the pickings from these imperialist wars tend to be hogged by the US, with only crumbs left for its European partners in crime, whose warmongering enthusiasm has consequently tended to be more muted.

For the most part, the European bourgeoisie would far rather do business with Iran than wage war against it. In these circumstances, being given orders by the US that perfectly normal banking business cannot be carried on with that country without the banks who carry on such business being sanctioned by Washington is not always well received:

“The Mayor ... referred to an email from a senior London-based Standard Chartered executive – thought to be finance director Richard Meddings – to a top official in the New York branch who raised concerns about breaching US sanctions on Iran.

“The email, the content of which was hotly disputed by the bank yesterday, allegedly said: ‘You ****ing Americans. Who are you to tell us, the rest of the world, that we can’t deal with the Iranians?’

“Mr Johnson said: ‘I disapprove of the language, of course.

“‘But I have to say – and I speak as the proud possessor of an American passport – that there seems to be something fine and sound about the underlying sentiment’.” (‘Stop beating up our banks, US is warned’ by James Salmon, Daily Mail, 9 August 2012)

What Boris Johnson was particularly concerned about, however, was the undoubted fact that the US regulators are going out of the way to try to ensure the maximum possible damage to London’s position as a world financial centre. The US would like the finance business that London attracts through its light regulatory touch and its generous tax treatment of billionaires to find its way to New York and provide all the jobs and tax revenues to America that are currently provided to Britain. To achieve that aim, it has naturally not the slightest hesitation in deploying the utmost hypocrisy to damage its British and European rivals. |